One Saturday morning, my father and stepmother sat the four of us down in the living room for a family meeting. Family meetings weren’t uncommon now since spankings and groundings had proven ineffectual. I was all the evidence they needed to see that all the discipline wasn’t working. Although I was unquestionably the least controllable, and certainly the angriest, we all rebelled in our own small ways.

Aaron’s fury often matched mine. David kept entirely to himself. He worked at the Ponderosa Steakhouse, saved up enough money for a small motorcycle, and more often than not, I’d go days without seeing him. Holly wasn’t angry, but she was directionless, floating, and too old now, at age 20, to really be disciplined for anything she did.

My father passed around a binder to each of us. The binders held a one-page typed list of rules, titled in all caps “TIME FOR A CHANGE.” There were eight categories:

1. Curfew

2. TV

3. Chores

4. Meals

5. Church

6. Counseling

7. Rewards for Excellence

8. Un-Christian words, deeds or lifestyles will not be tolerated here!!!

We had new curfews and wake-up times. Chores to be done by noon on Saturday. No jeans at church. No swearing. Dinner at 5:45 p.m. Snacks “as directed.” Counseling was required once per week and we were to make our own appointments; conveniently, there was a phone number. Under “Rewards for Excellence” we were instructed to find a hobby or a sport. “Improved grades, acts of thoughtfulness, going the way you should go” would also earn a reward, though the document did not offer specifics. No secular music, tapes, records, or posters “in house or on property.”

There was one single line, one allusion to what felt to me like a shattering admission: “No child or parent abuse (verbal or physical). Control your anger and your words.”

It was just two sentences buried in the document. But it gave me hope. What it said to me was that my dad bore some responsibility, too. That he had to try, too.

The document ended with an adage from my father: “If you are not self-disciplined, the world’s discipline will be painful. You are your own best friend or worst enemy. Go for it and become what you were made for. You can’t lose.”

Then, my father had written by hand a letter to each of us. This was mine:

You are attractive and intelligent. God made you beautiful inside and out. You have a sweet spirit and tender compassionate heart. You are creative and fun to be with. You have an inner strength and resolve to carry through to attain a goal. You have a good sense of humor and infectious smile and laugh. You are a leader and “A” student when disciplined to study and resolve to be the best at whatever you lay your hand to. I am blessed to have you as my daughter and proud of you. –Dad

Several years ago, I showed this document to my father. He couldn’t believe I still had it. It was dated September 14, 1985. As he read it, in my home office, I could see a darkness come over his face, and I had to leave the room to keep him from seeing me tear up, to keep from maybe seeing him tear up.

Because we both knew what happened next.

That night, Holly and I went up the street to Gina and Kelly’s house. Gina was Holly’s friend, and Kelly was mine. They lived with their mom and brother. Kelly was a year older than me with a flaming red afro and freckles and a wild, whole-bodied laugh. Sometime around 11 p.m., Holly and Gina took Holly’s green hatchback Citation to the White Hen Pantry for snacks. They should have been back in 20 minutes, but 20 minutes came and went. Then it was 11:30, and 11:45 and 11:55, and I froze, not knowing what to do.

I’d been sneaking in and out of this window for years now, but I assumed my father didn’t know.Our curfew was midnight. Should I abandon Holly and walk home? Or wait for her? Should I ask Kelly’s mom to call my dad? And say what? That Holly had gone out for snacks and wasn’t back yet? It felt wrong to just leave Holly on her own—and wouldn’t my parents have been angry with me for abandoning her? What if she was hurt? What if the White Hen Pantry had been robbed while Holly and Gina were in there with a bag of Doritos and a liter of Diet Coke?

Sometime after midnight, the phone rang at the Jimmink house and it was Gina saying there’d been a fender bender, and now they were in the emergency room and could Mrs. Jimmink pick them up? Holly’s car wasn’t drivable.

I called my father. He picked up without saying hello, his voice deep and groggy. “You’re late.”

“I know,” I told him, “but—”

“You’re late.” He cut me off. His voice had that impatient edge I’d come to recognize.

“No, but—”

“No buts,” he said. At other times it was something he’d say to get a laugh. He’d see half a cigarette on the ground and say, “No ifs, ands, or butts!”

“Holly had a car accident,” I blurted. I assumed this would change things. He’d soften his voice. He’d see that this time, at least, it wasn’t my fault.

“You’re late,” he said, and he hung up.

*

Once Gina and Holly returned, Mrs. Jimmink drove us the quarter mile to our house. It was 2 a.m. now, and the front door was locked. I wasn’t surprised, but I’d held out some hope anyway. It was a crisp fall night, the grass dewy as I walked through the front yard, making sure to avoid the black volcanic rocks that had once gashed open John-John’s knee. I made my way around the side of the house to my basement bedroom window. The window was locked. This was a surprise. I’d been sneaking in and out of this window for years now, but I assumed my father didn’t know. I’d never come home and found it locked.

My breathing got shallow, my hands starting to sweat. What does this mean? What will happen? I knew the back door would be locked, too, but I tried it anyway, tiptoeing up the deck stairs so Charley, our dog, wouldn’t wake up and bark.

Mrs. Jimmink said we could sleep at her house. It would all be sorted out in the morning. She couldn’t understand a parent who didn’t ask about his children after a car accident, she said. What was the matter with him? She felt so terribly sorry for us. Maybe my dad had been half asleep and hadn’t known what he was saying, Mrs. Jimmink offered. Maybe he hadn’t really been paying attention when I said the words “car accident.” But even as she presented these rationalizations, I knew the truth: he knew exactly what he was doing. Time for a change, his handout had said.

When Holly and I returned to our house the next morning, the front door was unlocked. We let ourselves in and nearly tripped over four empty suitcases lined up in the entryway. My father and stepmother stood at the top of the stairs watching us, their faces stern, final. “Pick one,” my dad told us. They were not interested in hearing more, in talking to us at all.

Our mirrored wallpaper offered fuzzy outlines of the scene, the shag-carpeted stairs, the railing slats, the four suitcases. I froze there for a long moment, my brain refusing to take in what I was seeing. The suitcases, the stiff line of my father’s face. Leave, I finally understood. Leave this house and don’t return. I could feel nausea threatening to erupt in my stomach, a chill starting at my fingertips and working its way into my body.

Holly was 20. Aaron was 17. The two of them went to their grandmother’s house in Geneva, a suburb a half hour to the west. David stayed with a friend for a month, and then he rented a room at the YMCA in downtown Naperville, where he would finish his last year of high school. But the equation—four kids, four suitcases—was an abyss for me, like staring into a lightless cave. I could not imagine any future life for myself at all.

I picked the most colorful suitcase, a dark blue and maroon soft-bodied Samsonite.

__________________________________

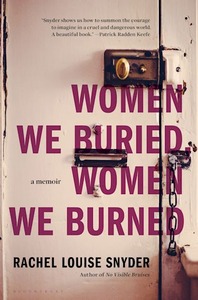

From Women We Buried, Women We Burned. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2023 by Rachel Louise Snyder.