Entrants to the 2021 SFR Writing Contest met the challenge of producing short works of fiction on the theme “Emerge,” and contest judge James McGrath Morris says choosing the winners was a “terrifying” challenge in itself.

Nevertheless, the biographer who has published numerous books spoke to SFR as he was driving back to New Mexico from Tulsa, part of the tour for his newest title, Tony Hillerman: A Life, which was published in October.

A connoisseur of fiction, McGrath Morris says he identified several components upon which to judge the stories: cohesiveness, turns of phrase that reflected sophisticated writing, use of telling details and sense of structure. The winning works each carry a degree of ambiguity and melancholy, he says, and each appealed to what’s been on his mind lately: loss.

“I’m 67. I tend to be more familiar with loss than I did when I was in my 20s so a fiction that speaks to loss as opposed to a fiction that emphasises beginnings subjectively influences my decision no matter what I do.”

Fiction works were required to use the words: fog, antiseptic and guardian. Next week’s cover story will feature the winners in the nonfiction category on the theme “What We Owe Each Other.”(Julie Ann Grimm)

FIRST PLACE

Send Me Dead Flowers

By Amy Purcell

The flower bulb arrived in a festive red cocoon. It looked like a cartoon bomb. Sonya brought it into the house, called Babs.

“Thank you for the—”

She didn’t quite know what to make of.

“Amaryllis,” Babs said. “Ignore it. It thrives on neglect.”

Sonya hung up the, guessed it was customary to give friends plants when their husbands asked for a divorce. Babs never failed to do the proper thing. What wasn’t customary, Sonya thought, was women her age getting a divorce. Women over seventy, decoupling after forty-five years, five dogs, three miscarriages (and no children), two cancer scares, seven houses and too many jobs to count.

She stared at this strange gift in her hand, imagined hurling it at Gene’s head, knocking some sense into him or knocking him out, the latter being her preference. She turned the ball over, read the tag on the bottom: It doesn’t get any easier than this! This wax-covered amaryllis bulb is completely self-sustaining! It will bloom with no care whatsoever! No water needed to bloom! Just place it on an indoor surface and watch it grow!

Despite the overuse of exclamation points, the flower sounded perfect. Forget those trendy succulents at Target. She and this amaryllis would be highly compatible. A plant that required no attention while she could find a place to call her own seemed like the most thoughtful, loving gift imaginable. She had nothing left to give and the bulb needed nothing given.

She ran her finger across the tiny green nub sprouting from the waxy prison, worried the negative vibes in the house would inhibit the flower’s ability to flourish, wondered if she should light a bundle of sage and smudge the room, something she hadn’t done in decades. Next, she’d be pulling out her old Tarot deck, the one that predicted she and Gene would marry. She shook her head. All that other-worldly nonsense was for the young ones; not she and Gene, retired the past five years, she volunteering at the animal shelter, he—well—he said he had been researching his family tree at the library. Maybe she should have followed him there, scouted out the young librarians.

She took the bulb to the spare bedroom where she’d been sleeping ever since D-Day last week. That still unbelievable morning when she’d been finishing her lackluster yoga routine, struggling with pigeon pose. Gene had crouched down on the floor, told her he was leaving. For good, he tagged onto the end of his declaration.

“You’re telling me this now?” she cried out.

“I wanted to make sure you wouldn’t run away,” he said.

Gene knew she hated pigeon pose, had to roll to her side to release herself from the hip flexing torture. She was too old for any of it, the yoga, his crazy talk.

She entered corpse pose as he outlined his rationale, his tone so antiseptic and rehearsed. Their marriage wasn’t working for him anymore. No excitement. No sex. Sonya drifted as he talked on, unable to listen to anything but the sound of the only adult life she had ever known cracking apart. She picked up his voice again when he trotted out the age-old line, “we’ve grown apart.” She winced at the cliché, at becoming a statistic, resisted responding with snarky remarks about his recent skinny jeans—not a good look—and dye job—also not a good look—to cover the grey of their impending grey divorce.

No, the spare bedroom was no place for Babs’s gift.

Sonya went to the sunroom, placed the bulb on the windowsill.

“I am gassing you now,” she whispered. “I mean ghosting. Whatever the kids say these days.”

Now she had attorneys to call, pensions to divide, no time to sort through her feelings as she sorted through decades worth of shared goods and shared friends to tell.

Babs called.

“Is it The Tinder?” Babs asked. “The Alzheimer’s? The Old Banana, if you get my drift.”

Sonya got Babs’s drift less and less these days. Babs had grandchildren and great-grandchildren that kept her younger than her seventy-nine years.

“None of the above,” Sonya said.

“How are you?”

Sonya stretched her neck side to side, thinking. “Death would be preferable over divorce. His, not mine. I’d rather be a widow. Easier to explain.”

Another week passed. Still no sprouting bulb. Still no yielding husband. When Sonya wasn’t stalking the plant for signs of growth, she stalked Gene’s credit card activity and his new Facebook page, found nothing out of the ordinary. Maybe it was The Alzheimer’s.

She texted Babs. The amaryllis is not to be trusted. It’s a fake. A liar. Rejecting me as its guardian.

Babs replied with a series of Bitmojis—one with her cartoon face on a black cat, another with a gold chain around her neck that said “Word,” and yet another where her hand was slapping her face with the letters FML beside her. Sonya looked that one up, wished she could find the person who invented that and thank them.

She read the scant instructions on the bulb again. No water needed to flower! She sprinkled water on top of the bulb anyway, then moved it to a brighter spot in the sunroom, opened her laptop. She scanned the first few pages of every self-help book on Amazon, Googled how to argue peacefully, how to manage rage, how to repossess her identity, how to be like Gwyneth Paltrow and consciously uncouple, how to get a stubborn amaryllis to bloom. FML. FML.

FYG.

Fuck you, Gene.

Several articles advised going “no contact” with Gene, promised that lack of contact often rekindled worn-out love. Sonya tried to apply the rule to both amaryllis and Gene, waited for a miracle. Gene still left the house in his skinny jeans. The flower still didn’t flower.

She called Babs again.

“It’s not working out,” Sonya said. “The amaryllis, I mean.”

Babs blamed it all on Gene as Sonya hoped she would.

“I’m on Team Sonya,” she said. “Team Sonya and Amaryllis no matter what.”

The next morning, a single sprout emerged from the papery folds at the top of the bulb. Hope! Renewal! Growth! Buoyed by this sign, Sonya carried the amaryllis outside, found Gene in the backyard doing calisthenics. She asked him one last time if he wanted to go to couples therapy. Try EMDR, an exorcist, Viagra. She showed him the amaryllis, tried using it as a talisman.

“Did you know,” she said, trying to make her voice sultry like Audrey Hepburn, his old crush. “Did you know that the name amaryllis first appeared in Virgil’s pastoral Eclogues? She was a shepherdess who represented both shade and light. Just like us. All marriages have periods of darkness and sparkle, Gene.”

He stopped mid-burpee, groaning. “I’m stuck, Sonya,” he said. In his pained face, Sonya read his meaning. No hope! No reconciliation! No change of heart!

Moving day loomed. Sonya stuffed her wedding dress into a box marked “Past; Do Not Open.” Taped up storage bins filled with old photographs. Mixed the ashes of their former dogs together and divided their remains in half. Called the movers twice to confirm they wouldn’t let her down.

She considered bringing the amaryllis to her new condo unit next to Babs, just a few miles from the home she’d known for forty years, but the new sprout looked like it was sticking its tiny green tongue out at her.

“Same to you,” she huffed, blowing raspberries at the plant as she slammed the door.

The morning of the move, Sonya visited the amaryllis in the sunroom. No sunlight yet, just fog lifting off the deck, the grass grey with haze, the color Gene’s hair should have been. She set the bulb on the old dining room table, the one they’d purchased when they first married, that heady time when she couldn’t fathom this being her future. Tears speckled the red cocoon, disappeared into the reedy top.

Following the instructions she’d read in one of the self-help books, she wrote down all her fears, her anger and confusion and sadness, everything she wouldn’t miss about Gene. She came up with only two things—the way his feet smelled moldy when he took off his shoes and how he always bought exactly what she asked for at Christmas. No imagination! No energy expended on thinking of her! No surprises! Then, who would find her if she fell in the new house? What if she forgot to change the batteries in the smoke alarm like Gene did every year? What about their European vacations? The times she wiped vomit from the corners of his mouth after chemo? How she’d weathered the dry months after his prostate had been removed? Would he remarry? Which friends would migrate to Team Gene? I love you. I hate you. I love you. FML. FYG.

She picked up the amaryllis and walked into the backyard. Once, when they’d vacationed in Taos, she’d read about a Native American ritual. Dig a hole in the Earth, then speak all of your ugly thoughts into the hole as a way of letting them go. This had come back to her when they’d argued over who got the Pendleton blanket, the one they’d fucked on all those years ago outside their tent, the Milky Way sparkling in the darkness above them.

Sonya dug a small hole, dropped the amaryllis to the ground, read everything she’d written aloud to the bulb, choking out the last three letters, “FYG.”

She picked up a handful of dirt, then hesitated. That red wax, that thick cage so tight around the bulb. Even if the flower would never bloom, the least she could do was liberate her from bondage.

Back in the kitchen, she pulled a knife from the drawer, slashed through the wax, each cut bringing relief. How she wished she could slip out of her own skin this easily, shed anything binding her to the past.

She peeled off the remaining wax. The bottom of the bulb had decayed, damaged beyond repair. When she cut the bulb in half, it resembled an onion. Layer upon layer of scarred white flesh. An amaryllis, she knew, got one shot. Blooming exhausts the bulb. Its life ends in beauty.

Except hers.

She returned to the yard and knelt beside the hole. She let the bulb, now divided in half, roll off her hand and into the ground. She covered her with soil. Sonya closed her eyes, lifted her face to the rising sun, asked the amaryllis to feed the beetles, worms, the roots of another flower. She imagined her, unable to bloom above ground, flourishing underground—fuel for another flower. She would emerge again, transformed by the elements that surrounded her.

She would bloom again. In time.

***

For over 25 years, I have split my time between writing corporate communications and, my first love, writing fiction. I returned to school in 2009 as a nontraditional student to obtain my M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Kent State University. My short stories have been published in Triquarterly, The Masters Review, Third Coast, Bosque Journal and The Writer Magazine, among others. I recently moved to Albuquerque, NM with my husband and two Australian Shepherds, and am currently working on a novel.

SECOND PLACE

Always with a Lime

By Cullen Curtiss

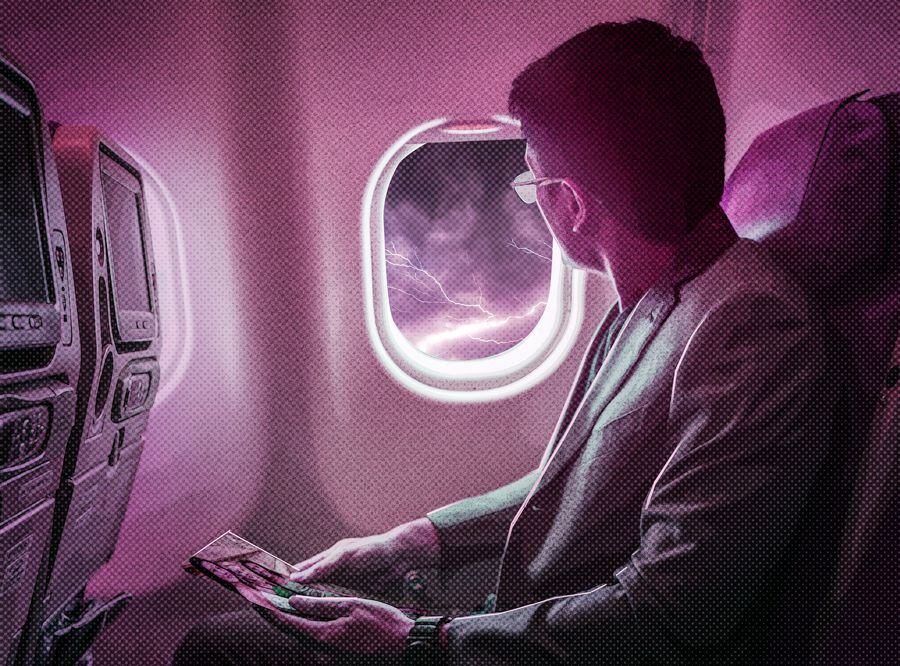

Were someone in the seat beside me, he or she would peer into my lap at this photograph of my daughters. My slight, knowing smile would show that I understand I am lucky.

“Lovely. Your daughters are lovely indeed.”

That would be the end of my peace. I would be queried until the flight touched down in Rio de Janeiro. Schools, boys, dreams. I would share what I know, which is not as much as I’d like.

But this afternoon in First Class, I have only myself to answer to, not to some chatty traveler with a briefcase. Nice that my last flight should be exactly as I like, despite the heavy rains and wind.

“Mr. Kittredge? A vodka tonic?”

I hold the picture against my chest.

“Thank you, Marcia. In a tall glass, with a lime.”

“Of course.”

Marcia knows I have three daughters, but she is professional, and will pry only when I’ve given a little, like last week when I asked her to stow my coat in the overhead bin. I said I couldn’t do it because the pain in my shoulder was fierce and she asked why, and we went on from there about my trip to Miami for a weekend of golf. I’ll miss her service; she makes a damn good drink and her perfume is not musky, like the other’s.

I unfasten my seat belt and cross my ankles. Colleagues ask what I’ll do with my free time. Play golf. Those already retired tell me that I’ll likely lose a little of my identity without the job, without the title and the expense account. What they don’t know is that I am a golfer more than I am anything else. And using the logic that would necessarily follow, my plans for retirement will put me in better “touch” with who I am.

“Your drink, Mr. Kittredge.”

“Thank you, Marcia.”

She turns and I smell her perfume, or maybe it’s been her soap all this time.

“By the way, Marcia. This is my last flight to Rio de Janeiro. I thought you should know.”

“Well, Mr. Kittredge, it has certainly been a pleasure. I’ll miss our chats.” She looks at the picture I’ve left on the tray table. “More time to spend with those beautiful girls of yours.”

People tell me they are beautiful all the time. They are; their mother is. But this picture is particularly good. I took it because my wife can’t take a decent one. Caught up in the moment of reunion or celebration, she forgets about the sun, the flash, and people’s feet, but she’s good at backdrops. In Venice years ago, she corralled them into one end of the boat next to the gondolier. The girls tease her about picture time, but I know they love her for it, for embarrassing them in public, for tucking their hair behind their ears.

I adjust the light above my head and then re-fasten my belt as directed. The plane is not steady. I carefully take a big sip of my drink to keep things under control. Not that it matters now, but I never took to wearing jeans or a running suit when traveling for business like some colleagues — it seemed tacky to me, but I’ll bet their dry-cleaning bills are lower.

I’m startled when a passenger behind me lets out a little scream. Seems a flight attendant has capsized a Bloody Mary on her. Not surprising given the plane’s hairy ascent through the cloud cover.

Yes, this is a perfect picture. It is August of last year and my daughters are tan. I finally notice the thing about the dresses that I’ve overheard my wife exclaiming to friends and relatives over the phone. Each one has a different pattern and a completely different style, but they are the same colors: blue, white, and black. “And they didn’t even plan it!” my wife says. “Only sisters could do that!”

I see myself most in my eldest, Daphne. A round face with dark eyes. She is 25, but I still see her in a pink snowsuit pointing at a plane in the sky and shouting, “Daddy!” I guess she’s always pointed to things and called them something else. With that talent, she’d like to be a writer and I don’t really blame her. That life sounds more interesting than banking, which is what I do, but I have trouble advocating such a fickle pursuit. In the one story she’s let me read, the father worked odd construction jobs, was divorced, had a live-in girlfriend, and was legal guardian to an Afghan refugee child. I know so little about how fiction works.

My daughters are sitting very close together on a stoop and they have their arms linked. They’ve always been affectionate — I don’t know where that comes from.

That’s a lie. I do know. It comes from their mother, who coddles them to no end, afraid she’ll be construed as the antiseptic woman she thought her mother was.

Daphne occasionally hooks her arm around mine when we are walking. At first, I was taken aback, but now I rarely see her. She has always tried hard to make bridges — she used to give me and her mother the cold shoulder when we fought. If I were brave enough to explain how irreconcilable things happen between people. I guess she will learn that from someone else in time.

We are flying above the fog and clouds now. The sun is strong and buoys my mood, not to mention that it puts me at ease. I am reminded that I’m leaving the February winter of the northeast for another hemisphere where it is summer and I don’t speak the language, not even after all these business trips. The time to learn would obviously have been a while ago. I’ve recently thought about the kind of relationships I might have formed if I had taken a beginner course.

“Mr. Kittredge? Another vodka tonic?”

“You’re good, Marcia.”

“Just doing my job,” she says and winks. “But I envy you, retiring early — what I wouldn’t give to see more of my son … if he’d have me.” She puts a hand on her hip. “Kids have so many other priorities these days, you know?”

I stare at her for a second longer than is polite. I don’t know the answer to her question, but I say something that surprises me. “Deep down I think we all know family is the most important thing, don’t you?”

But she must attend to someone emerging from the cockpit and mouths, “Sorry.”

I can see where the sun has touched a small section of the wood door behind my middle daughter’s head. Although it lights all of their faces, I think there is a certain justice that it should warm and glow on the wood above Nicole’s head. As a middle child, she’s been characteristically frantic, not knowing which direction to go. I’m not sure I’ve helped to point a way. When she invited me to lunch last summer, I don’t know who was more nervous. We were finishing our lattés when she finally got to her point. She asked to borrow money to get her teaching degree, and then placed a spreadsheet in front of me, and explained the repayment schedule she’d devised. What she doesn’t know is that I would have given her money to start an exotic ant farm. I don’t know how people get these things across to one another. I’ve thought of asking my golf partner who has two daughters, how he handles it.

While driving back to the office alone that day, I recalled how Nicole used to read to imaginary students for hours. She couldn’t have been more than seven or eight, just learning to read herself. Sitting on the edge of the toilet, she spoke slowly and clearly to a bathtub full of bright-eyed pupils. Though she looked like a boy for a long time, with dark bangs and a bony body, there’s no confusion any more; she resembles most the Native American Indian princess I have on my side of the family.

The arched door behind the girls is that of a church in the South End of Boston. My wife kept our table at a restaurant across the street while the girls posed. Daphne would return to California and her book publishing job the following morning and my youngest, Clancy, would begin her first week as an assistant account executive at an advertising company. Nicole would be teaching at a new elementary school come September.

It’s fitting that Clancy is most aggressively pursuing the camera — her short, blonde haircut looks so smart. She is such a go-getter. The top half of her short-sleeved dress is all black and it’s a nice, conservative contrast to the bare shoulders of Daphne and Nicole, who sit on either side of her. I think she is tired of my teasing her about her power suits. Though I offered, she wouldn’t let me pull any strings for her when she graduated from college last spring. She said, “Thanks, Dad, but I’d like to take the credit.” I’ve analyzed that one a dozen times, something I criticize my wife for doing. But such an exercise can only remind you of your insecurities.

I know that my wife made a mental note of my asking for a picture to take on this trip. I have never asked for anything like that before. I do know where she keeps this sort of thing — I could have just taken one. She will tell our daughters that I wanted their picture with me on my last trip and maybe the gesture will mean something to them.

Darkness comes over the cabin and I look out the window to see that we are approaching some undeniably sinister weather. Marcia passes quickly in the aisle and shoots me a glance. I tighten my seat belt and squeeze the lime again before finishing my drink. I will not be up here so often any more. My wife won’t fly. She says she’d rather die any other way than falling out of the sky. At the moment, I understand what she means. The captain is telling the flight attendants to be seated.

Maybe we’ll take a road trip to California this summer to see Daphne’s new house, or maybe we can all converge somewhere in Montana at one of those dude ranch places. I think the girls would like that. Or better yet, a spa. That would probably be more appropriate. Perhaps I’ll call my wife the minute this bird is safely on the ground and see what she thinks of the idea. Some of those spas even have golf courses, but maybe it won’t matter.

***

Hailing from the East Coast, Cullen is happy in her adopted home, among friends, family, and the great outdoors. She writes for a living.

THIRD PLACE

Seeing What You See

By Martha Burns

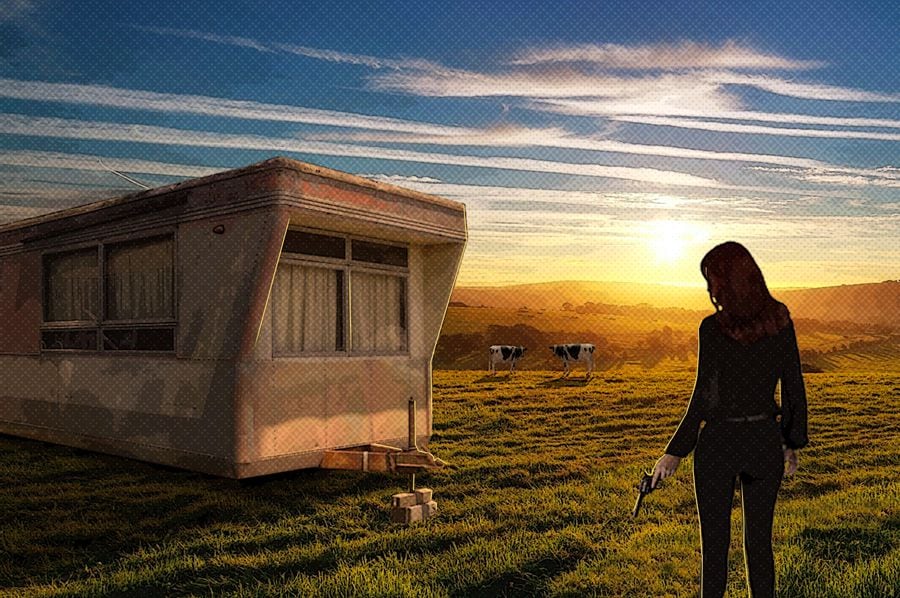

Linda Pruitt’s column, Views from the Ranch, went to press once a week. Linda was a genuine ranch woman. She knew her livestock, her sheep dogs and could put a sturdy meal on the table. The Ruidoso Ledger referred to her as a local girl. Neighbors seemed to have no inkling trouble was brewing in Linda and Payton Pruitt’s marriage; said they were shocked by the deaths.

Her final column appeared in Ranching Weekly on February 23, 1995. A person could find the Weekly lying around all over southeast New Mexico, but especially in Roswell at the livestock auction. A strangely artistic, close-up photo of a single cow was often featured on the front page.

As Linda submerged her cold, hardened hands in the hot suds that February morning, she looked out the Plexiglas window, and waited for the feeling in her hands to return.

“The world was never out to ruin you, Payton Pruitt,” she’d said aloud to him the night before as he came in the back door of their trailer, smelling of manure, looking for his supper. He’d rubbed the back of his baked red neck and screwed up his stiff face like she was a nut job. Then she whispered to his back as he went down the stubby hallway, “You did that all on your own, cowboy.”

Living all those twenty-seven married years, fifteen miles from nowhere, Linda Pruitt had finally come to a point. Nothing scared her in those weeks after she decided, not even seeing her grown sons with their loaded .38 Special on their hips. Well, she’d agreed to raise them around loaded guns, and an unloaded gun was no better than a rock, Payton said, so who could she blame? A peace that she could not describe settled in on her. That was good because she had plenty of things to get done.

She had wanted her own house and a real glass window over the kitchen sink. She didn’t need the land to be hers. That was a silly way to think anyway. Just her own house with a big, east-facing picture window and one room she could paint green. But she was not a cattle queen, and there was zero chance she was going to have that. She wouldn’t miss this sad excuse for a house, but she would miss calving season. No two calves were ever alike, and all the mamas, fierce defenders, knew their own.

She dried her hands and took a step away from the sink and sat at her kitchen table, turning her thoughts to her column. She loved pencils and paper. She licked the lead and tapped the page as she read what she had rearranged, reassembled, straightened out, and finally typed the day before. She didn’t make a single mark. She settled the pages and paper-clipped them.

She needed to be outside, always needed to clear out the fog of fact and fiction in her brain after she finished a column. She opened the kitchen drawer. She had insisted on calling it that even though her sons had liked to call it the junk drawer. She pulled out a plain white envelope and felt for her roll of thirty-two cent Love stamps. She took three of them and placed them carefully side by side on the envelope. She addressed the envelope to the Weekly, folded the pages of her last column neatly, and slipped them into the envelope. Then right below the stamps she wrote AIR MAIL in block letters, and she laughed for the last time in her forty-eight years. Nobody heard.

Linda stepped out the front door of the trailer and whistled for the dog. Cattlemen and woolgrowers were pretty proud of their dogs but not Payton Pruitt. He never did give the best dogs much credit. Trixie was hers.

The dog heard her and poised to scat as if Linda was giving fair warning that Payton was close by. The dog lived in fear of him and got lost every night when Payton turned off the highway onto the dirt road. Linda took off a glove and stroked the collie’s fine head before heading out to the mailbox a mile down the loop road.

Linda had a pretty good idea where she’d gone wrong with her two sons. She’d let her boys see her face be bruised and blackened by their father’s hand—so many times—too many times. It wasn’t right what she had done to them. She’d been a poor guardian. Meanness could be a catching thing that no after-the-fact antiseptic could erase.

“Goodbye to all that,” she said because she liked talking to the dog.

Linda tucked the envelope way back in the box, lifted the red flag, and sat right down on the dirt with her back up against the post. Then she started wishing real hard for someone to come driving by. She considered counting her blessings and even started with her grandson, Leeland, but quit, because what she kept remembering was driving down this unpaved, sunbaked road with Payton, their sons, Stralin and Luke, in the back of the extended cab—telling him to stop for the mail. And then Payton reaching his thick arm across her, shoving open her door and pushing her out.

She needed to get back home and get out to feed the horses and see about supper, but Trixie moved close, checked the narrow loop road left and right, lowered herself down and leaned against her. Linda whispered in the dog’s ear, “Hush now.”

Linda did not have to tell her hand to pull the trigger of the cold revolver. She was grateful for that and grateful for the few hours she would have all to herself that night. And, of course, grateful not to be worried about one single thing. Payton was gone, a gunshot to his left temple. He was right-handed, and she didn’t want any confusion for the Chaves County Sheriff. The evidence had to point to her as the killer, that she was the only one to blame.

She had simply said, “Goodnight, Payton,” and thought of a green room, and then she shot him, but no one would ever know that tantalizing tidbit.

She tasted blood and closed the hollow bedroom door behind her and stepped into the tiny bathroom to splash her face with cold water like her mother had taught her to do whenever she was feeling flushed.

Linda had never considered poison. Shooting Payton close up like that felt justified and inevitable, natural like, even if it was the dreadful side of a natural thing. And for a few seconds, standing there before the veined bathroom mirror, enthralled maybe with her own clean face, she toyed with ideas for her column, ways she might write about that perfectly natural thing she’d done. Then she told herself that this topic, even if she turned it into a fairy tale of self-reliance, would be too gritty for her readers, and she got her mind off that quick.

How she’d loved her readers.

Linda went over to the front door and turned off the yard lights. Then she opened the door just enough to slip through and not let too much light out. She needed to see the stars. She tried to coax Trixie over. The dog gave her the eye, the look Trixie always used to control the stock, back when Payton let her do her work, and then crept on her belly right up to Linda to sniff her hand.

Linda said, “Don’t be afraid. You’ve seen the last of him.”

Trixie took off, circled the yard clockwise and then counterclockwise, let out one plaintive wail and headed up the road to the gate. Seeing Trixie take off made Linda sad. She should have tied her up. She closed the door but didn’t lock it. The front gate wasn’t locked either, only dummy locked. It saved all the hands a lot of trouble.

Linda made herself a cup of hot tea and wrote two letters, one for each son. The letters weren’t suicide notes, but they’d get called that. There’d be a lot of detective-talk here at the ranch headquarters the next morning. Nothing she could do about that. Her home would be a crime scene.

Reporters would come out to do their tantalizing job—leaving no stone unturned.

After she finished up with that one last part of her plan, she listened to the night highway noise up on the road she couldn’t see, heard the approaching 18-wheeler, and then the next, and then she didn’t hear any noise anywhere.

In that silence, something dawned on her that must have made her feel like the happiest person she had been in forever. She opened Luke’s letter and wrote on the bottom: “Son, find Trixie and give her to Leeland to protect. Let the dog teach your son how to look out for an innocent creature, and you watch out for that boy. See what you see.”

Readers of Linda Pruitt’s column will be saddened, as we at Ranching Weekly were, to learn that Linda and her husband, Payton, passed away last week. Many of our readers identified with Linda’s column, because she related so sincerely the pleasures and frustrations of ranch life. Hers were the heartfelt observations of someone who’d been there and done it, and who’d do it again in a minute. Payton Pruitt had been employed by the Diamond Crown Ranch of Roswell for 15 years, and Linda wrote her ‘Views’ column for the Ranching Weekly.

The Ranching Weekly featured that piece on their front page, right beneath a black and white photo of a single cow standing in a mushy winter field. Linda probably would have seen something in that photo the rest of us missed.

****

I was born and raised in Albuquerque where I graduated from UNM with a degree in math, but soon I was off to Hawaii and then to California and onto New Jersey and Switzerland before returning to New Mexico. While in New Jersey I earned a Doctor of Letters from Drew University. I’ve studied with writers: Robert Boswell, Pam Houston and Minrose Gwin. I won first prize in the Faulkner-Wisdom award for my short story “Something Rotten.” I’ve completed a novel, Blind Eye, and a screenplay by the same title. I’m hopeful the novel will be published in 2022. My career as a CPA in international tax provided me the opportunity to work on interesting issues with people from many different countries. My husband and I are the parents of two adult daughters. We split our time now between Santa Fe and La Luz, New Mexico in the Sacramento Mountains.