We’ve all watched a honeybee fly past us and land on a nearby flower. But how does she know what she’s looking for?

And when she leaves the hive for the first time, how does she even know what a flower looks like?

Our paper, published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, set out to discover whether bees have an innate “flower template” in their minds, which allows them to know exactly what they are looking for even if they’ve never seen a flower before.

Read more: One, then some: how to count like a bee

A story of partnership

Plants and pollinators need each other to survive and prosper. Many plants require animals to transport pollen between flowers so the plants can reproduce. Meanwhile, pollinators rely on plants for nutrition (such as pollen and nectar) and nesting resources (such as leaves and resin).

As such, flowering plants and pollinators have been in partnership for millions of years. This relationship often results in flowers having evolved certain signals such as colours, shapes and patterns that are more attractive to bees.

At the same time, bees’ reliance on flower resources such as nectar and pollen has led them to be effective learners of flower signals. They must be able to tell which flowers in their environment will provide a reward and which will not. If they didn’t know the difference, they would waste time searching for nectar in the wrong flowers.

Our findings show bees can quickly and effectively learn to discriminate between flowers of slightly different shapes – a bit like how humans can expertly tell faces apart.

The amazing brains of honeybees

Honeybee brains are tiny. They weigh less than a milligram and contain just 960,000 neurons (compared to 86 billion in human brains). But despite this, they demonstrate exceptional learning abilities.

Their learning extends to many cognitively challenging tasks, including maze navigation, size discrimination, counting, quantity discrimination and even simple math!

Read more: Bees join an elite group of species that understands the concept of zero as a number

So we know bees can learn all sorts of flower-related information, but we wanted to discover how they find flowers on their first foraging trip outside the hive. We also investigated whether experienced foragers developed a bias in their foraging strategies and flower preferences.

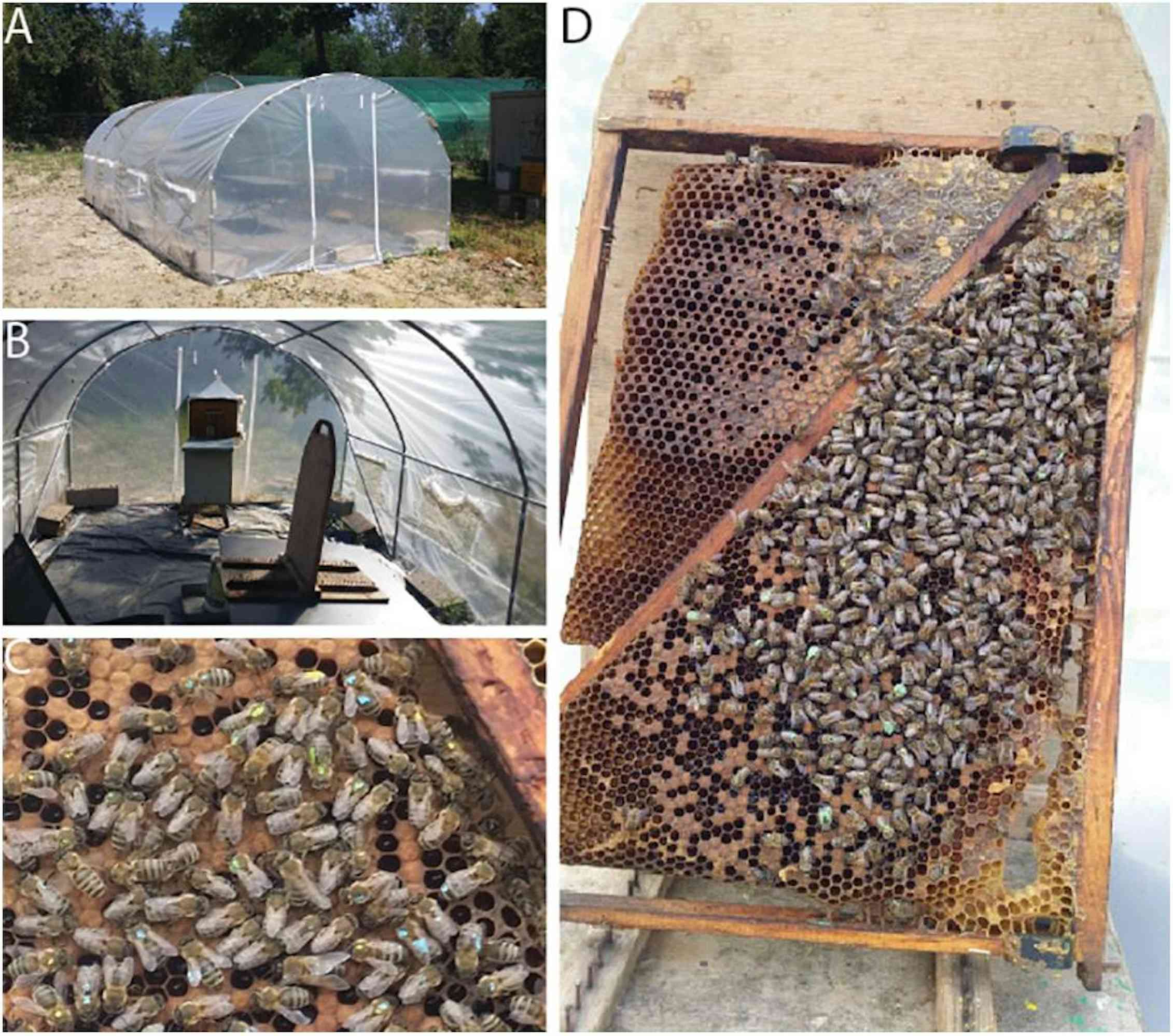

To test this, we prompted two groups of bees to discriminate between sets of flower images. One group was raised in a hive inside a greenhouse with no flowers, and had therefore never been exposed to flowers. We put a colour mark on these bees at birth, so we could track them once they emerged from the hive to forage two weeks later.

The second group consisted of experienced foragers which had encountered many flowers in their lives.

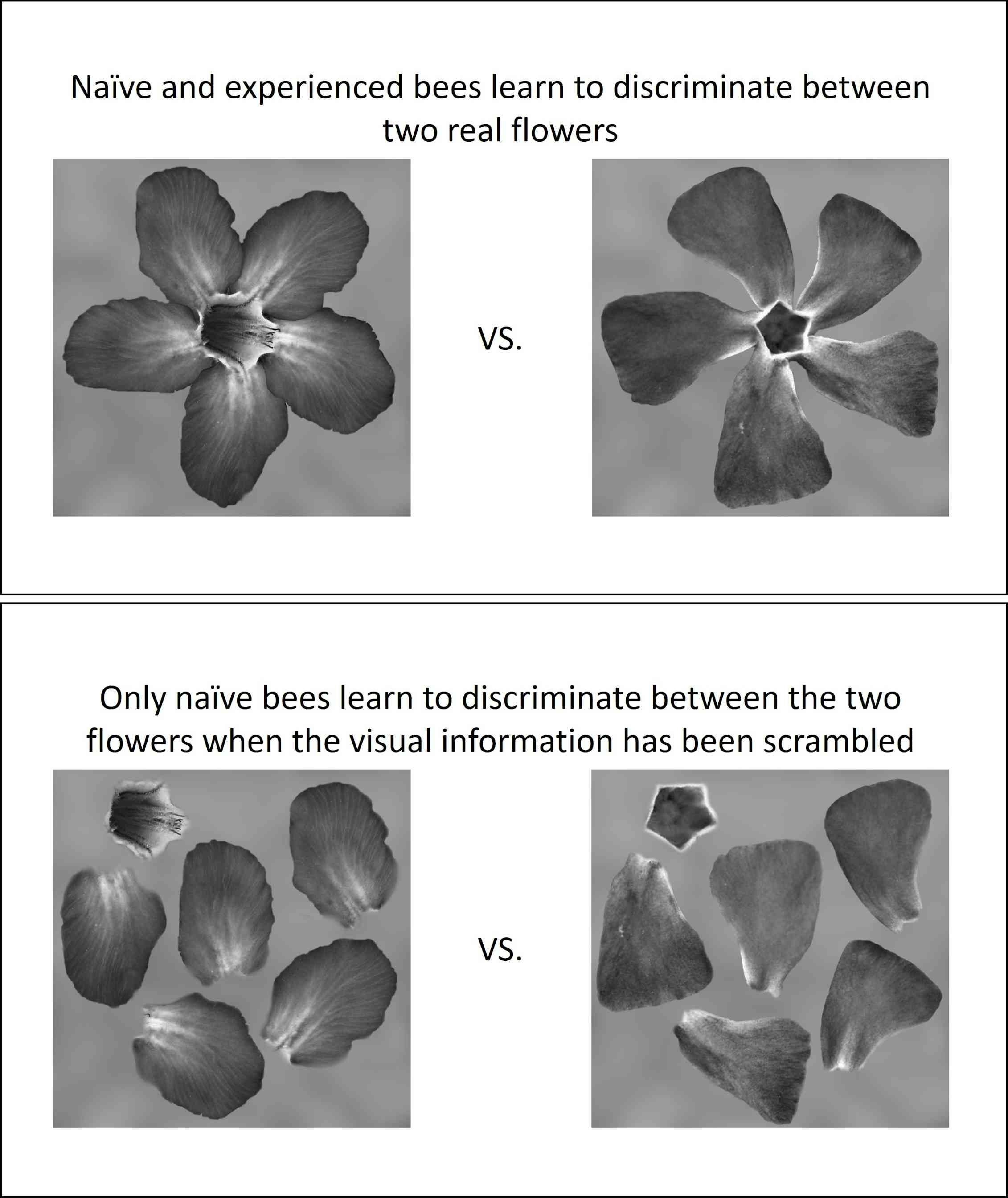

We trained both groups to discriminate between images of two flowers found in nature, using a reward of sugar water for choosing the correct option when directed. We also trained both groups to discriminate between the same flowers with the petals separated and randomly scrambled.

How well and how quickly the bees learnt to discriminate between the images of whole flowers, versus how long they took to discriminate between the scrambled petals, would tell us which information they preferred to learn.

Both the flower-naïve and experienced foragers learnt to discriminate between the images of whole flowers better, and more quickly, than the scrambled petals. However, the flower-naïve honeybees appeared to have less bias as they also learnt to discriminate between the scrambled information, while the experienced foragers could not.

The results reveal flower-naïve bees have an innate flower template that aids them with learning new flowers and discriminating between them. At the same time, experienced foragers become biased towards certain flower shapes as they gain foraging experience.

Overall, bees use an innate flower template to first find flowers, and also draw on their past knowledge as they become more experienced.

Innate recognition in other animals

While our findings on honeybees are remarkable, they do tie into similar capabilities in other species.

Different species have evolved brains which tune into important stimuli. For example, humans and other primates can detect, process, recognise and discriminate between the faces of other members of their species. Research has shown even human infants can detect and recognise other people’s faces very well.

Our preference for faces, and ability to recognise them, has probably evolved due to the importance of needing to discriminate between friends, enemies and strangers. This is akin to the bees needing to process images of whole flower shapes better than scrambled petal images – due to the importance of recognising flower shape for survival.

Similarly, social paper wasps evaluate their relationship with hive-mates based on the different facial markings of friends and foes. Just like bees, they do this using a combination of innate mechanisms and lived experience.

Scarlett Howard receives funding from the Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, and the Fyssen Foundation. She is affiliated with Pint of Science Australia.

Adrian Dyer receives funding from The Australian Research Council.